Original Jersey City Skeeters

With a population of 206,000 at the turn of the 20th century, Jersey City was one of the world’s most important freight terminals, and grew rapidly in the years leading up to the First World War (268,000 by 1910, 294,000 by 1914). Thanks in no small part to the popularity of the Skeeters, the city had 23 formally organized amateur baseball teams in the last years before the war, one of which, “The Grandpops”, appears to have been the first all-grandfather team in baseball history. (The Jersey Journal, April 19th, 1909) Baseball reigned unchallenged as the king of sports in the area, as it did throughout most of the US.

In 1902 the Jersey City Skeeters (officially the Jersey City Ball Club) set up their franchise in the Eastern League, renamed the International League in 1912. The Baltimore Orioles, Buffalo Bison, Rochester Bronchos (or Hustlers), Montreal Royals, Toronto Maple Leafs, Providence Grays, and the Newark Indians rounded out the league, which was perhaps the strongest league below The National League and The American League. The Eastern was one of fourteen baseball leagues that formally recognized each other in 1902 and helped to standardize the sport. The Eastern League cities had the highest population base of any of the leagues below the Majors, which guaranteed the league prominence. The teams were independent, not farm teams of major league clubs. Indeed, they would scavenge a few players each from the major league clubs once the latter set their rosters and cast off 10-20 promising players at the end of spring training. Eastern League play began around April 21st each year, and ran for up to 140 games, depending on the year. Teams would make some extra cash playing major league clubs in exhibitions, even during the season, on Sundays.

The Grounds

Jersey City’s 8,500 capacity West Side Park hosted the Skeeters near the Jersey Central Rail Station. Nature imposed the Skeeters nickname on the club—the struggle versus mosquitoes being serious enough to warrant occasional coverage in the local papers of the day. The club caught on very fast, with Opening Day becoming a semi-official holiday in Jersey City. Newspapers trumpeted the occasion on page 1, and factories closed after a half day, allowing fans to get to the stadium, or to sturdy trees with a view of the field, or just to the parade route leading to West Side Park. Big crowds always turned out to see exhibition games against the New York Giants or other major league squads, and also for Eastern League games versus local rival Newark. As sportswriter G.A. Brakely once put it, “Jersey City would rather beat Newark than get a Presidential convention. And it’s vice versa, by the way.” (The Jersey Journal, May 18th, 1909) The Skeeters nickname was of no help in selecting a mascot, so the team settled on a Bull Terrier that did tricks for the crowd (such was the case in 1909, anyway).

The Mascot

1903: The Recordbreaker

The Skeeters covered themselves in glory in 1903, to the point that in 2001 Minor League Baseball crowned the 1903 Skeeters the 7th greatest minor league team of the 20th century. The team won its first 16 games, then ripped off a streak of 24 straight late in the season to vault from four games behind first-place Buffalo and build a 10 game lead. The Skeeters finished 92-33, a .736 winning percentage, with four 20-game winning pitchers.

Russ Ford’s Emery Ball—the greatest freak pitch of all time?

"(Russ) Ford, a most intelligent fellow, had an odd delivery that was almost unhittable. He had an overhand swing that was noticeably good ... his form was not up to that of the really great pitchers. Still, he would send a ball up at the batter that would suddenly dart away…" - Ty Cobb in Memoirs of Twenty Years in Baseball (Ty Cobb, 1955)

The Jersey City Skeeter who left the deepest mark on baseball history (pun intended) was Manitoba-born right-handed pitcher Russell Ford. Ford joined Jersey City in 1909, and in that year he pioneered his vicious “emery ball”. Ford would put a dime-sized abrasion on one side of the ball, which gave straight fastballs a wicked cut as they neared the plate. He mastered his creation—a feat very few freak pitch inventors could claim--and it vaulted him to the American League in spectacular style.

Ford turned in what was surely one of the greatest rookie seasons of all-time with the New York Highlanders (Yankees) in 1910. He went 26-6, with an ERA of 1.65, 209 strikouts, and a tremendous 0.881 WHIP (walks plus hits per inning pitched) that year. The legendary Christy Mathewson and Grover Cleveland Alexander are the only other pitchers ever to have notched 20 or more wins and 200 strikeouts in their rookie seasons. His career era of 2.64 places him in the top 60 in baseball history (the ranking varies depending upon eligibility criteria, such as innings pitched and the chronological cut-off in the 19th century); his 2.54 ERA in a New York uniform remains the franchise record (or second best, if one includes reliever Mariano Rivera).

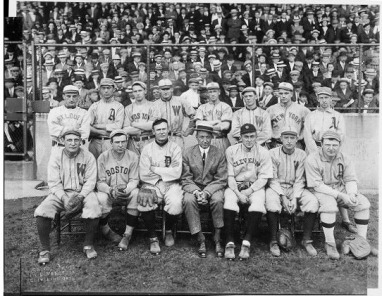

He was dominant enough at his peak, in fact, to join Walter Johnson and Smoky Joe Wood as the only three pitchers on the second ever American League all-star team, assembled in July 1911 to play a benefit game after the sudden death of Cleveland’s great pitcher Addie Joss—there he is with a slew of Hall-of-Famers, second from the right in the rear row (the first American League all-star team played an exhibition series against the National League Champion Pittsburgh Pirates after the 1902 season).

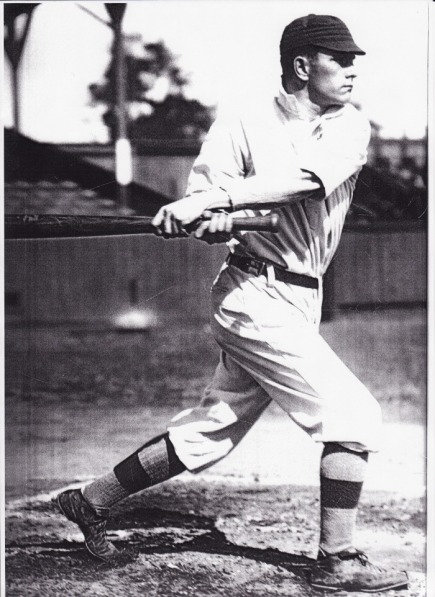

Russ Ford at the plate, West Side Park, Jersey City, 1909

Ford was masterful in a Jersey City uniform, right from his first start on May 13th, 1909, when he scattered four-hits in a 4-1 complete game win over Toronto. His biggest day came on June 11th, when he shut out Montreal over 15 innings, winning 1-0. He was of course a fan favorite, but was not flamboyant in any way. Perhaps because he had something to hide (his freak pitch), Ford was very composed on the mound, but egregious umpiring could provoke him, and he found himself ejected twice while hurling for the Skeeters.

Ford hid his invention very well. As a contemporary recalled, “He had a hole in his glove and under it was a piece of emery paper. Then he wore a ring on his finger with a piece of emery paper wrapped around it. The ring was on a rubber band, and when he pulled it off, it went up his sleeve.” {as quoted in Donald Honig, Shadows of Summer, 1994, p. 55}. Ford’s creation was the first pitch major league baseball would ban, after the 1914 season.